Directory

Original Paper Introduction Historically Contemporary ConclusionPlease feel free to click on whichever button you need to get you a to certain point within the essay. Please note that the bibliography and Original Paper buttons will lead you to a PDF off this main website.

For any randos who are reading this who are not my professor, hi :3c. For any classmates reading this, please check out the guest book.

Women in Hinduism: Historical and Contemporary:

Introduction

Hinduism is a religion that has spanned well over 4000 years, being considered one of the oldest religions still around in the world. With time, religions grow and change as people change. This includes the roles of women. Many Hindu texts and traditions have been used all throughout to either uplift or subdue women such as the Varalakshmi, which historically has done both, depending on the culture that interprets it. Time also helps to shape the interpretation of these texts to mark a woman's role in Hinduism. Another important aspect is the fact that divine, powerful Goddesses exist within Hinduism, such as Parvati, Durga, and Kali, just to name a few. The existence of such gods suggest the divine nature of femininity, making the history of how women are viewed within the religion a little complicated, especially amongst more patriarchal societies. Despite the intricacies, there are still major differences in how women were seen and their role within different time periods. Although Hinduism contains powerful ideals of feminine divinity, the lived roles of women have shifted dramatically across history, moving from relative ritual and educational authority in the Vedic period, to diminished status in the medieval era, and then to renewed visibility and participation in the modern age.

Hinduism is a religion that has spanned well over 4000 years, being considered one of the oldest religions still around in the world. With time, religions grow and change as people change. This includes the roles of women. Many Hindu texts and traditions have been used all throughout to either uplift or subdue women such as the Varalakshmi, which historically has done both, depending on the culture that interprets it. Time also helps to shape the interpretation of these texts to mark a woman's role in Hinduism. Another important aspect is the fact that divine, powerful Goddesses exist within Hinduism, such as Parvati, Durga, and Kali, just to name a few. The existence of such gods suggest the divine nature of femininity, making the history of how women are viewed within the religion a little complicated, especially amongst more patriarchal societies. Despite the intricacies, there are still major differences in how women were seen and their role within different time periods. Although Hinduism contains powerful ideals of feminine divinity, the lived roles of women have shifted dramatically across history, moving from relative ritual and educational authority in the Vedic period, to diminished status in the medieval era, and then to renewed visibility and participation in the modern age.

Historically

Vedic Age:

The Vedic era had a rather interesting view of women. Influenced by early concepts of feminine divinity found in the Vedic hymns, women during the Vedic period enjoyed privileges such as education (including teaching roles), involvement in politics, and a certain level of independence. However, it is important to note that education regarding the Vedas and Hindu philosophy seemed to be relegated to unmarried women and girls at this time. According to Role of Women in Ancient India by Naresh Nout, in ancient India, "There were two types of scholarly women -- the Brahmavadinis, or the women who never married and cultured the Vedas throughout their lives; and the Sadyodvahas who studied the Vedas till they married."(1) This is rather specific wording. While the text I'm using does not outright state that women absolutely *have* to be unwedded to be scholars, the wording implicates that it was the norm for scholarly women to be unmarried, compared to men who can be both married and scholars. The text further supports the notion that philosophy and religious studies was mainly for unmarried women and girls when recounting the story of Kousambi princess, Jayanti, "who remained a spinster to study religion and philosophy,"(2) once again insinuating that married women were somehow restricted from higher education in religion. Evidence of women being involved in politics is also prevalent. For example, “Megasthenes mentioned the Pandya women running the administration."(3) That combined with descriptions of two women taking role as queen in place of their under-aged sons gives the impression of women having much greater autonomy compared to later eras, which was certainly true early on in the Vedic era. However, as the era continues and goes into an early classical period, a woman's role became much more subdued, and their equal status to men was very quickly diminishing. A major reason for this shift can be found in interpretations of Rig Vedas and how they outline what a woman's role should be. Another place these shifts in attitudes towards women can be found is within Brahmana literature where "woman, the Shudra, the dog, and the black bird (the crow), are untruth,"(4) essentially comparing women to dogs and placing them in the same ritual purity as them. Depictions of women as being inferior to men are written multiple times throughout the text, signifying the start of a cultural shift in a woman's role within Hinduism, a shift that becomes religious doctrine.

The Vedic era had a rather interesting view of women. Influenced by early concepts of feminine divinity found in the Vedic hymns, women during the Vedic period enjoyed privileges such as education (including teaching roles), involvement in politics, and a certain level of independence. However, it is important to note that education regarding the Vedas and Hindu philosophy seemed to be relegated to unmarried women and girls at this time. According to Role of Women in Ancient India by Naresh Nout, in ancient India, "There were two types of scholarly women -- the Brahmavadinis, or the women who never married and cultured the Vedas throughout their lives; and the Sadyodvahas who studied the Vedas till they married."(1) This is rather specific wording. While the text I'm using does not outright state that women absolutely *have* to be unwedded to be scholars, the wording implicates that it was the norm for scholarly women to be unmarried, compared to men who can be both married and scholars. The text further supports the notion that philosophy and religious studies was mainly for unmarried women and girls when recounting the story of Kousambi princess, Jayanti, "who remained a spinster to study religion and philosophy,"(2) once again insinuating that married women were somehow restricted from higher education in religion. Evidence of women being involved in politics is also prevalent. For example, “Megasthenes mentioned the Pandya women running the administration."(3) That combined with descriptions of two women taking role as queen in place of their under-aged sons gives the impression of women having much greater autonomy compared to later eras, which was certainly true early on in the Vedic era. However, as the era continues and goes into an early classical period, a woman's role became much more subdued, and their equal status to men was very quickly diminishing. A major reason for this shift can be found in interpretations of Rig Vedas and how they outline what a woman's role should be. Another place these shifts in attitudes towards women can be found is within Brahmana literature where "woman, the Shudra, the dog, and the black bird (the crow), are untruth,"(4) essentially comparing women to dogs and placing them in the same ritual purity as them. Depictions of women as being inferior to men are written multiple times throughout the text, signifying the start of a cultural shift in a woman's role within Hinduism, a shift that becomes religious doctrine.

Hinduism in Patriarchal Societies:

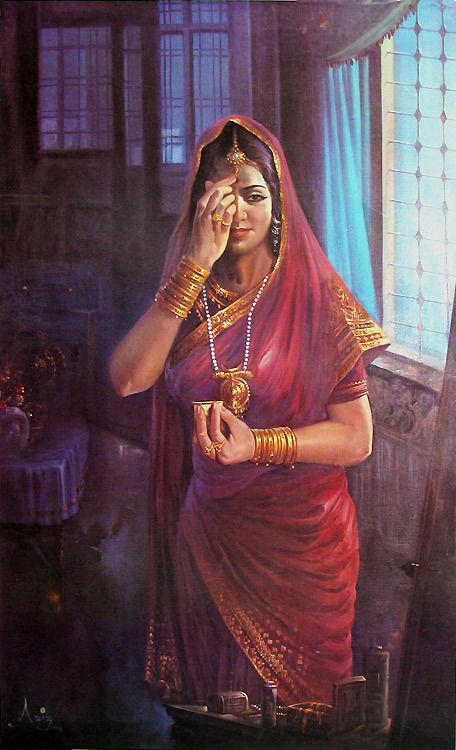

Most Hindu communities in early medieval India became increasingly patriarchal, emphasizing a woman's dependence on male guardians at each stage of life. A woman's utmost purpose was often framed as serving her husband, and many texts and customs promoted life-long fidelity to a single spouse. Unless a woman belonged to a high caste or an affluent family, she was typically barred from higher education, excluded from most public rituals, married at a young age, and described in certain ritual texts as being ritually inferior--even compared to impure beings and animals in some Brahmana passages.(5) This shift in women's status had multiple causes, but two major influences were the reinterpretation of earlier scriptures and the social changes brought by political upheavals and interactions with new ruling powers, including Islamic dynasties, whose own gender norms shaped aspects of medieval Indian society. The rituals women were allowed to take part in at this time reflected these. Rituals pertaining to health, family, and fertility were highly encouraged. One of the most infamous examples of this is Sati, which "refers to the ceremony of dying on the husband's funeral pyre," allowing her to go straight to paradise along with the deceased, and was, "seen as a preferable alternative than widowhood in Hindu society."(6) While this ritual was technically not mandatory in the few regions that allowed it, doing it was seen as a great honor for communities that partook in it. Of course, many regions did not pressure this onto women, although other customs such as shaving the head of a widow her putting her son in charge of her were still done as ways to signify her subservience.

Bahtki Movement's Impact:

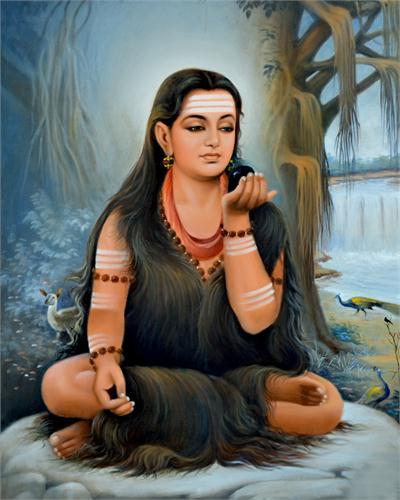

That being said, things got better for women in certain regions overtime. The Bhakti Movement, for example, sought to emphasize personal ritual for everyone regardless of caste or gender. In turn, "Its emphasis on personal devotion over ritual and its challenge to Brahminical orthodoxy provided women an opportunity to engage with spirituality directly and assert their voices."(7) The Bhakti Movement gave rise to Saints within Hinduism. One such saint is Akka Mahadevi, who was a Hinduist poet in the 12th century. Her poems focus on worshipping Shiva, whom she called Chennamallikarjuna. She wrote about Shiva as if he was her lover in her writings. Her poems also, "challenge[d] not only male dominance but also societal norms governing female behavior,"(8) by renouncing earthly authorities by stating that the self is enough, something unusual for a woman at the time to do. Another woman who subverted gender expectations at the time had also subverted caste expectations through the Bhakti movement. Janabai, a Dalit woman, wrote about her experiences as a servant and the pain her social standing brought her. In her writings, "she imagined God participating in her household chores, blurring the lines between sacred and mundane." Through humanizing god in such a way, Janabai "inverted traditional hierarchies and placed the divine within the sphere of feminine labor,"(9) putting established patriarchal religious foundations to question. While the Bhakti Movement did not completely eliminated patriarchal or caste systems, it did allow women some wiggle room to express themselves both personally and religiously.

That being said, things got better for women in certain regions overtime. The Bhakti Movement, for example, sought to emphasize personal ritual for everyone regardless of caste or gender. In turn, "Its emphasis on personal devotion over ritual and its challenge to Brahminical orthodoxy provided women an opportunity to engage with spirituality directly and assert their voices."(7) The Bhakti Movement gave rise to Saints within Hinduism. One such saint is Akka Mahadevi, who was a Hinduist poet in the 12th century. Her poems focus on worshipping Shiva, whom she called Chennamallikarjuna. She wrote about Shiva as if he was her lover in her writings. Her poems also, "challenge[d] not only male dominance but also societal norms governing female behavior,"(8) by renouncing earthly authorities by stating that the self is enough, something unusual for a woman at the time to do. Another woman who subverted gender expectations at the time had also subverted caste expectations through the Bhakti movement. Janabai, a Dalit woman, wrote about her experiences as a servant and the pain her social standing brought her. In her writings, "she imagined God participating in her household chores, blurring the lines between sacred and mundane." Through humanizing god in such a way, Janabai "inverted traditional hierarchies and placed the divine within the sphere of feminine labor,"(9) putting established patriarchal religious foundations to question. While the Bhakti Movement did not completely eliminated patriarchal or caste systems, it did allow women some wiggle room to express themselves both personally and religiously.

Hinduism in Matrilieneal Societies:

Despite how patriarchal Hinduism seemingly is, there are a few matrilineal Hinduist societies. Khasi and Garo (Meghalaya) are two notable ones. A Matrilineal society is a community where lineage, inheritance, and property pass through the female line. This automatically puts women on a higher pedestal compared to other Hindu communities. That being said, it is important to note that these groups are not matriarchies, which puts women in power over men. The reason women in these regions have such power has less to do with Hinduism and more to do with history.

"As warriors who often battled with other groups for land, Khasi men often went down to the plains for clashes. During those battles, some men died. Others settled for a new life in the plains. Left without their partners, Khasi women would remarry or find other partners, and it often became difficult to determine a child's paternity." (10)

While modern day Khasi is mostly Christian, these traditions have historically held true for their Hinduist populations.

Contemporarily

20th Century India:

During the British rule of India, and continuing well after independence, India introduced several major legal reforms with the goal of improving the status of women. Acts such as the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929, the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955, and the Hindu Succession Act of 1956, which all aimed to get rid of long-standing practices like early marriage, limited divorce rights, and unequal inheritance. Although these practices persisted socially, the laws marked a major shift toward recognizing women's rights, particularly within Hinduism. The 20th century also expanded women's access to both secular and religious education, allowing some to participate in Vedic learning and even pursue roles as gurus and priestesses, both of which were traditionally restricted to men. Women's organizations, especially the All India Women's Conference, sought to expand these rights even further. Founded in 1927, the conference sought to push for reforms in education and consent laws, arguing that delaying the marriage age so girls can pursue education and personal independence was a worth-while process. These shifts created space for women to become more visible within Hindu religious life, which can be seen by figures such as Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, founder of Sahaja Yoga who championed for women's inherent power and responsibility in society. These changes mark a new level of visibility for women, as they were generally no longer seen as property for men to onw. While there are still plenty of Hindu communities that insist on old traditions of marriage and barring women from Vedic ritual--such as the Paharia Tribes, modern Hinduism as a whole see women as their own persons who are not inherently ritually unclean

During the British rule of India, and continuing well after independence, India introduced several major legal reforms with the goal of improving the status of women. Acts such as the Child Marriage Restraint Act of 1929, the Hindu Marriage Act of 1955, and the Hindu Succession Act of 1956, which all aimed to get rid of long-standing practices like early marriage, limited divorce rights, and unequal inheritance. Although these practices persisted socially, the laws marked a major shift toward recognizing women's rights, particularly within Hinduism. The 20th century also expanded women's access to both secular and religious education, allowing some to participate in Vedic learning and even pursue roles as gurus and priestesses, both of which were traditionally restricted to men. Women's organizations, especially the All India Women's Conference, sought to expand these rights even further. Founded in 1927, the conference sought to push for reforms in education and consent laws, arguing that delaying the marriage age so girls can pursue education and personal independence was a worth-while process. These shifts created space for women to become more visible within Hindu religious life, which can be seen by figures such as Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi, founder of Sahaja Yoga who championed for women's inherent power and responsibility in society. These changes mark a new level of visibility for women, as they were generally no longer seen as property for men to onw. While there are still plenty of Hindu communities that insist on old traditions of marriage and barring women from Vedic ritual--such as the Paharia Tribes, modern Hinduism as a whole see women as their own persons who are not inherently ritually unclean

Conclusion:

Hinduism throughout its thousands of years of being has lend a hand in both female empowerment and female oppression, depending on the era and interpretation of religious texts. What started as a religion that held women in high regards, turned into one that saw women as nothing more than property, turned into a tool for female autonomy and empowerment. Plenty of movements to this day still continue to break down barriers for women within Hinduism, allowing for a more equal field in it. While acknowledging the fact some communities are still stuck in viewing women as unclean or to be owned, it cannot be understated just how far majority of Hinduist communities have come to liberate women.

Footnotes:

- Nout, Naresh Role of Women in Ancient India. Odisha Review, January 2016 pg. 42

- Nout. Role of Women in Ancient India. pg, 42

- Nout. Role of Women in Ancient India. pg, 43

- Satapatha Brahmana 14.1.1.31.

- Khare, Disha. Status of Women in Medieval India. Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education Vol. 16, Issue No. 2, February-2019, ISSN 2230-7540 Page 2-3

- Khare, Disha. Status of Women in Medieval India. Journal of Advances and Scholarly Researches in Allied Education

- Achmare, Rashmi. Gender, Devotion, and Dissent: The Role of Women Saint Poets in Challenging Patriarchy. May 2025. Seagull Journals Vol. 2 Issue 5. Page 2-3

- Achmare. Gender, Devotion, and Dissent. Page 2

- Achmare. Gender, Devotion, and Dissent. Page 3

- Rathnayake, Zinara. "Khasis: India's indigenous matrilineal society". March 21, 2021. BBC

- Nair, Usha.” AIWC at a Glance: The First Twenty years”. Slide 3.

- Dr. Chatterjee, Esha. Exploring Gender Dynamics in Hinduism through Activism and Reform, Page 3-4